Mencius & Diogenes — Virtue and Humanity

Downloads & Resources

Mencius & Diogenes — Virtue and Humanity

Two Worlds, One Question

Artistic comparison of two ancient centres of study: the Imperial Examination Hall in Guangzhou and Aristotle’s Lyceum in Athens. Both sought wisdom through discipline — one through moral cultivation, the other through rational inquiry — echoing a shared human pursuit of truth. (Artistic Impression based on archaeological and historical sources.)

Two minds on opposite sides of the ancient world — Mencius in China and Diogenes in Greece — asked the same question:

what does it mean to live rightly?

One sought virtue within the structure of duty.

The other found freedom through defiance.

But both stood at a turning point in history — an age when moral insight was being replaced by political power, and learning was shifting from wisdom to rule.

Their answers reveal a truth humanity keeps rediscovering, then forgetting:

that moral strength outlasts every empire.

The century of foundations

The 4th century BCE was an age of architects — not of stone, but of systems.

Across continents, the foundations of the modern world were being poured.

In China, the Warring States tore each other apart in pursuit of dominance, while scholars like Confucius and Mencius tried to rescue civilisation from its own ambition.

In Greece, the city-state was giving way to empire, philosophy was turning into profession, and thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, and Diogenes fought to remind the world that wisdom was not the same as cleverness.

It was the moment when humanity began to trade intuition for institution.

Parallel lives, divergent paths

Thousands of miles apart, Mencius and Diogenes lived different lives but shared the same condition — exile, frustration, and a relentless hunger for moral clarity.

Mencius, born amid political chaos, carried the teachings of Confucius from one warlord’s court to another, arguing that compassion, not conquest, was the true mark of civilisation.

Diogenes, cast out from his home for defacing currency, took to the streets of Athens, declaring that it was society itself that had become counterfeit.

Both faced the same question: when the world rewards power and conformity, how does a person remain free?

One spoke to kings; the other mocked them.

One built moral philosophy into governance; the other dismantled hypocrisy with laughter.

But beneath those differences ran the same pulse — an insistence that truth cannot be owned, sold, or institutionalised.

The courage to live your philosophy

To Mencius, living rightly meant cultivating the heart — nurturing compassion until it guided every act of leadership.

To Diogenes, it meant stripping life to the truth — shedding every false need until only integrity remained.

Both saw that morality had to begin not in temples or laws, but in how a person walked through the world.

Neither wrote manifestos for the powerful; both wrote by example.

Their philosophies survived because they were lived — one in the court, one in the marketplace.

And if they met in some imagined space beyond time — the scholar in robes and the beggar with a lamp — they might have recognised each other instantly.

Both, after all, were looking for the same thing: an honest human being.

Yuan Dynasty portrait, National Palace Museum, Taipei (Public Domain).

Mencius — The Politics of Compassion

(Part II of “If We Reached the Same Truth Thousands of Miles Apart”)

He was born into a fractured world. China’s Warring States period (475–221 BCE) was a time of relentless conquest and moral collapse — a world in which power was measured in acres and armies, not virtue. Amid that chaos, Mencius (孟子 – Mengzi, 372–289 BCE) asked a question that still echoes through history: what is government for, if not to protect the humanity of its people?

A childhood shaped by loss and moral learning

Mencius was born in the small state of Zou, in what is now Shandong province. His father died when he was young, leaving him in the care of his mother, who became one of the most revered figures in Chinese folklore. Known simply as Mencius’s Mother (孟母), she raised him with unwavering devotion to both learning and moral strength.

When their first home stood near a cemetery, the young boy imitated funeral rites in play. His mother moved the household near a marketplace, but soon saw him copying merchants’ haggling. Only when she settled beside a school did she stop — there, Mencius began to imitate scholars in study.

The parable, “Mencius’s Mother Moves Three Times,” became one of the most enduring lessons in Chinese education. It taught that character is cultivated by environment — that education is not confined to books, but to the soil of example.

Another story tells of her cutting through her weaving in front of her distracted son. “If you abandon your studies halfway,” she said, “you are like me cutting through this cloth.” Learning, she taught, is continuous, not convenient.

In these maternal parables lies the heart of Mencius’s thought: morality must be lived into being. It is not imposed by law; it is nurtured by practice.

Walking the courts of power

As a young man, Mencius was schooled in the Confucian classics, studying under disciples of Confucius’s grandson, Zisi. Yet where Confucius sought harmony through ritual and tradition, Mencius sharpened those teachings into a moral philosophy of governance.

He travelled from court to court, advising rulers who were more interested in profit than in virtue. The Book of Mencius records these encounters in a dialogue style — intellectual sparring sessions that reveal as much about the speaker’s integrity as his wit.

When King Hui of Liang asked what profit Mencius could bring to his state, the philosopher replied simply:

“Why speak of profit? All I speak of is humanity (ren) and righteousness (yi). If Your Majesty says, ‘How may I profit my state?’, your officials will say, ‘How may I profit my family?’, and your people, ‘How may I profit myself?’ Soon the state will be torn apart.”

To Mencius, profit was the seed of division. Compassion, by contrast, was the root of unity.

He did not deny hierarchy; he redefined it. Power existed to serve, not to dominate. If a ruler failed to act benevolently, he lost what was called the Mandate of Heaven — not divine privilege, but the moral license to lead.

The goodness of human nature

The core of Mencius’s philosophy lies in his radical belief that human nature is good.

Where many saw humanity as selfish or corruptible, he argued that each person is born with moral “sprouts” — four beginnings:

Compassion (the heart that cannot bear the suffering of others),

Shame (the heart that rejects wrongdoing),

Courtesy (the heart that yields to others),

Discernment (the heart that knows right from wrong).

These are not learned virtues; they are inherent capacities, needing cultivation as plants need sunlight.

To neglect them is to starve the moral self; to nurture them is to become fully human.

He illustrated this with a simple image:

“Suppose a person suddenly sees a child about to fall into a well. He will feel alarm and compassion — not for the sake of friendship or fame, but because it is human nature to feel it.”

From this, Mencius built an entire moral cosmology: governments must reflect the moral instinct of the heart. To rule without empathy is to act against human nature itself.

Education as the cultivation of virtue

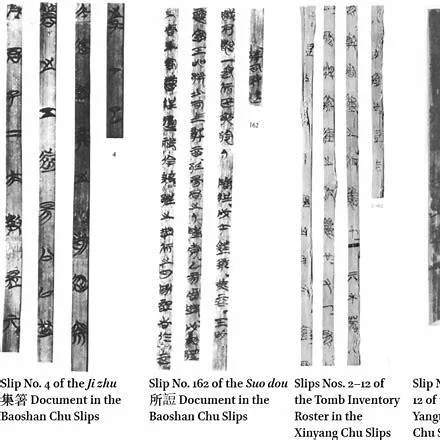

In Mencius’s time, education was becoming formalised, but he resisted the idea of learning as mere scholarship.

For him, education was the art of moral cultivation — the shaping of one’s xin (心), the heart–mind.

To memorise the classics without embodying their principles was to miss the point entirely.

He believed that the ultimate purpose of study was moral strength, not status. A learned man who exploited others was more dangerous than an uneducated one, because his intellect lacked compassion to anchor it.

This stands in stark contrast to the later bureaucratic model of education — the imperial examination system that would, centuries after his death, claim to uphold his teachings while reducing them to rote memorisation.

Historic photograph showing the remaining courtyard structures (Public Domain).

Mencius wanted reflection; his successors built recitation.

He sought humanity; they built hierarchy.

In this lies the enduring irony of his legacy: his philosophy of compassion became the foundation for a system that measured obedience.

The politics of empathy

Mencius’s political vision was not utopian — it was practical, even revolutionary.

He argued that just rule could bring prosperity without coercion.

Reduce taxes, care for the elderly, and people would give loyalty freely.

In one debate, when a ruler asked how to win the hearts of his people, Mencius answered:

“Treat them as you would your own children, and they will stand by you as by their parents.”

It was not sentimentality; it was strategy rooted in humanity.

Govern with empathy, and you create stability. Govern through fear, and you breed rebellion.

His vision of leadership prefigures later democratic ideals — government by consent, not by divine decree.

Legacy — The moral spine of East Asia

Over centuries, Mencius’s ideas became the backbone of Confucian humanism.

When the philosopher Zhu Xi in the 12th century formalised the Four Books — the Analects, Mencius, Great Learning, and Doctrine of the Mean — he elevated Mencius to near-saintly status.

His teachings spread beyond China to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, shaping not just politics but family ethics, social conduct, and education.

Even today, his phrases echo in East Asian values of harmony, duty, and social balance.

But the deeper message transcends culture: Mencius redefined power as a moral act.

He saw humanity as a web of interdependence — rulers, teachers, and citizens bound by conscience rather than fear.

In his world, a good society was one where virtue outweighed victory.

Reflection

Mencius’s voice still feels startlingly modern.

He might not have imagined parliaments or constitutions, but his principle is timeless: a leader who forgets compassion forfeits legitimacy.

He saw education not as the training of clerks, but the awakening of conscience.

He believed the purpose of knowledge was not to divide people into ranks, but to reunite them in understanding.

And through his mother’s parables — of weaving, moving, and nurturing — he left behind more than philosophy:

he left a map of how societies grow hearts as well as minds.

Diogenes — The Philosopher of Defiance

(Part III of “If We Reached the Same Truth Thousands of Miles Apart”)

If Mencius believed that humanity could be refined through compassion, Diogenes of Sinope (c. 404 – 323 BCE) believed it could only be revealed through rejection.

He stripped life down until nothing unnecessary remained — no possessions, no pretense, no false reverence.

Where others lectured on virtue, he lived it like a dare.

Exile and awakening

Diogenes was born in Sinope, a Greek colony on the Black Sea, the son of a banker named Hicesias.

A scandal ended his comfortable life: he and his father were accused of debasing the city’s coinage — a literal corruption of value that became, for Diogenes, a lifelong metaphor.

Banished from his homeland, he arrived in Athens as an exile and began questioning everything society minted as “genuine.”

He found in Antisthenes, a disciple of Socrates, a teacher who shared his contempt for luxury.

Antisthenes refused him at first, even striking him with a staff.

Diogenes supposedly replied, “Strike, for you will find no wood hard enough to keep me away if I think you have something to say.”

That stubborn pursuit of truth defined his life.

Athens, the so-called cradle of reason, was to Diogenes a city of polite hypocrisy — a place that praised moderation while worshiping wealth.

He chose to live instead in the streets, sleeping in the agora, eating what he could find, and conversing with whoever would listen.

His home, it is said, was a discarded pithos — a giant clay jar.

To Athenians it looked like madness; to Diogenes it was liberation.

The dog philosopher

From those days he earned the nickname kynikos — “dog-like.”

What began as mockery became the badge of a new school: Cynicism.

The philosopher depicted living in a barrel (pithos), surrounded by dogs — his chosen companions and symbols of honest simplicity.

He embraced the comparison completely.

Dogs, he said, live honestly: they eat when hungry, bark at deceit, and recognise friends without ceremony.

Why, he asked, should humans be ashamed to do the same?

The Cynic life demanded autarkeia — self-sufficiency — and anaideia — freedom from false shame.

To need little was to be free; to pretend was to be enslaved.

When he saw a child drinking from cupped hands, Diogenes threw away his wooden bowl:

“A child has beaten me in simplicity.”

He begged in daylight, mocked the grandiose, and exposed hypocrisy through performance.

When Plato defined man as “a featherless biped,” Diogenes plucked a chicken and marched into the Academy declaring,

“Here is Plato’s man.”

Plato amended his definition to add “with broad flat nails.”

Every act was philosophy embodied.

He showed that ideas mean nothing if they cannot survive in daylight.

Truth in provocation

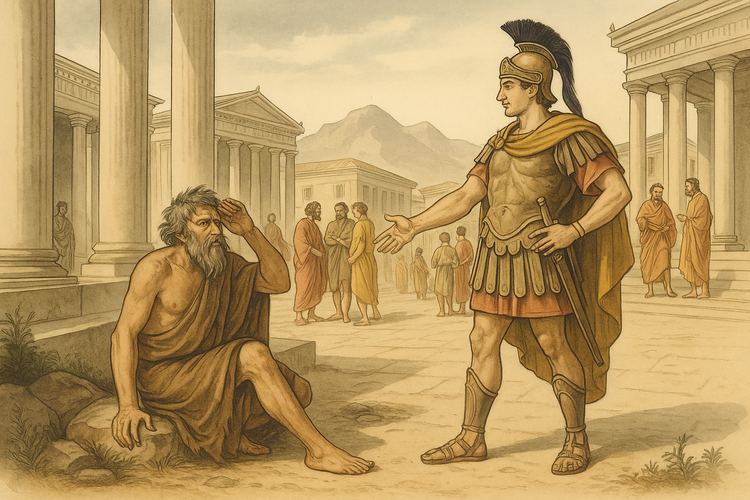

Diogenes’s most famous gesture came when Alexander the Great visited him in Corinth.

The young conqueror stood before the filthy philosopher and said, “Ask of me any favour.”

Diogenes, lying in the sun, replied,

“Stand out of my light.”

That reply, casual and cosmic, condensed his entire worldview:

power cannot grant what it does not possess.

Freedom is not bestowed; it is lived.

When asked where he came from, he answered,

“I am a citizen of the world.”

It was the first recorded use of the word cosmopolitan — a vision of identity that transcended city, race, and empire.

Diogenes turned philosophy outward — from classroom debate to moral theatre.

He ridiculed greed not by speeches but by sleeping in doorways.

He taught integrity not by essays but by example.

He made truth uncomfortable — and therefore visible.

Philosophy of freedom

Underneath the ridicule lay a disciplined system of ethics.

He believed that virtue was the only true good, and that external goods — wealth, reputation, social position — were not only irrelevant but dangerous.

They distracted the soul from its natural state of simplicity.

He echoed his teacher Antisthenes in claiming that happiness (eudaimonia) comes from living according to nature.

To live naturally is to live truthfully; to live truthfully is to need almost nothing.

He called this practice askēsis — training.

Just as athletes train the body, philosophers must train the soul through hardship:

cold, hunger, ridicule, and solitude were his weights and distances.

Through them he built moral strength.

For Diogenes, poverty was not deprivation; it was purification.

He sought to prove that a man who conquers himself is greater than one who conquers a continent — a quiet rebuke to Alexander’s empire-building frenzy.

Influence and inheritance

The lamp Diogenes carried through Athens did not go out with him.

His students, including Crates of Thebes, passed the torch to Zeno of Citium, who founded Stoicism.

The Stoics transformed Cynic defiance into civic virtue: where Diogenes barked at corruption, Stoics codified integrity into reason.

From that lineage came Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius — emperors and slaves alike tracing their moral ancestry to a man who owned nothing.

Cynicism also left subtler traces.

Early Christian ascetics adopted its simplicity; Enlightenment satirists borrowed its wit; modern minimalists echo its rejection of excess.

Even civil disobedience, from Thoreau to Gandhi, bears the Cynic imprint — the belief that moral authority grows stronger the less it depends on institutions.

Character and courage

What made Diogenes unique was not poverty but consistency.

He lived precisely as he preached.

He exposed corruption by refusing to participate in it.

He had no possessions to defend, no office to lose, no mask to maintain.

That radical independence made him untouchable — and, paradoxically, deeply influential.

He did not hate civilisation; he pitied it.

He saw people enslaved not by tyrants but by appetites.

“Other dogs bite their enemies,” he said, “I bite my friends to save them.”

The bite was metaphorical — a jolt back to honesty.

He barked against hypocrisy so that others might wake from it.

Philosophy as performance

Every generation produces reformers who try to change society from within.

Diogenes worked from the outside, using laughter as his weapon.

He turned public spaces into classrooms and himself into a mirror.

In him, philosophy returned to its origin: the love of wisdom, not its ownership.

He reminded Athens that thought must touch life to matter — that truth is not found in the academy but in the act.

Legacy of light

When asked what he wanted done with his body after death, Diogenes said,

“Throw me outside the city walls, so the beasts may eat me. I will not mind, since I will be without sensation.”

Even in death, he mocked the vanity of monuments.

Yet history built them anyway: statues, paintings, marble busts, and moral traditions that still carry his spark.

Diogenes offered the world a mirror polished by austerity.

In it we see what remains when everything false is stripped away:

a human being, unowned, unashamed, and unafraid to speak truth to power.

If Mencius taught us to rule through compassion, Diogenes taught us to live through conscience.

Both, in their ways, rebelled against the corruption of the age.

Both, in different languages, said the same thing:

freedom begins when we stop needing permission to be good.

Section 3 — The Same Truth in Different Tongues: A Global Convergence

Across continents and centuries, the same question kept rising from the human heart: how should a person live when the world measures worth in power?

Mencius answered through duty and compassion; Diogenes through defiance and simplicity.

Their distance makes the symmetry impossible to ignore.

When Mencius taught that a ruler’s greatness lay in mercy, and Diogenes declared that freedom required nothing but honesty, neither could have known the other existed.

Yet both were confronting the same dilemma: what remains of conscience when civilisation forgets its purpose?

This was not imitation but convergence — separate cultures striking the same moral chord.

Their worlds could hardly have been more different.

One spoke to kings, the other to crowds; one argued for order, the other for liberation.

Yet both understood that integrity cannot be delegated.

Compassion in the heart of a ruler and truth in the heart of a rebel are expressions of the same moral law: that a life is measured not by wealth or status, but by the truth it chooses to live.

To Mencius, humanity began in the ren — the capacity to feel another’s suffering as one’s own.

To Diogenes, it began in autarkeia — the courage to need nothing false.

Together they map the two halves of freedom: responsibility and self-restraint.

One sought to civilise power; the other to strip it bare.

Both believed that goodness could not be imposed from above or inherited from birth — it had to be cultivated from within.

Their parallel insights reveal something larger than philosophy: a pattern of conscience that reappears wherever human beings tire of being told what virtue means.

Civilisations rise independently, yet when each reaches its own crisis of meaning, the response is similar — a turn inward, a rediscovery of the heart.

It is as if the moral instinct is not cultural at all, but biological: the species remembering itself.

They also remind us that the story of ideas is never linear.

While scholars chase origins, wisdom keeps re-emerging, as if truth were a spring that cannot be buried for long.

Every empire that tries to own it merely proves the need for rediscovery.

This convergence is not coincidence but continuity.

Across time, conscience evolves independently wherever people face the same inequities and refuse the same lies.

Mencius tried to humanise authority; Diogenes tried to humanise life itself.

One built a system of compassion; the other dismantled systems to reveal compassion’s core.

Together they show that morality survives geography — it grows wherever people ask not What is permitted? but What is right?

Their dialogue was only one voice in a greater conversation.

While China and Greece were finding their moral languages, other civilisations were composing their own — each in a different key, yet all tuned to the same harmony between self and society.

🌍 Echoes Around the World

In India, sages of the Upanishads taught that truth lies within the self, not in ritual — “The Self is the altar, and the mind its sacred fire.”

Soon after, the Buddha walked among kingdoms urging compassion over caste, echoing Mencius’s belief that empathy is the seed of justice.

In Persia, Zoroastrian thinkers framed ethics as Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds — a triad close to Mencius’s virtues and Diogenes’s simplicity.

Far west, Egyptian and Nubian traditions preserved Maat — balance, truth, and rightness — as the law of both cosmos and conscience.

Across the ocean, in the civilisations of the Americas, moral order often meant harmony with the natural world rather than mastery over it.

Everywhere, the same compass surfaced: empathy, honesty, balance.

Civilisation depends not on conquest or creed, but on the capacity to act justly.

🪶 Reflection

The parallels remind us that equality was never invented; it was remembered.

Every society has, at some point, known that worth is measured by choice, not by category.

The tragedy is not that we failed to discover this truth, but that we keep forgetting it.

Closing Insight — The Lantern and the Mandate

Mencius carried the moral mandate; Diogenes carried the lamp.

Both searched for the same thing — a world lit by conscience.

Wisdom, they show, is never owned by a culture; it reappears wherever someone chooses understanding over pride, courage over comfort, truth over approval.

These voices prove that humanity’s deepest insights are not inventions of nation or era, but rediscoveries of the same light.

And that light still burns.

Equality, education, and basic humanity remain possible — not because we have advanced beyond division, but because the same capacity for empathy endures beneath it.

Each generation rediscovers the question that bound these two ancient seekers: what does it mean to live rightly?

Our task is to answer it again, in our own fractured century.

“Next, the journey continues — from virtue to knowledge.

In Alexandria and Lu, two teachers would face a question just as timeless:

how do we protect truth when power decides who may teach it?”

© Darren Palmer — Author of History Waits to Be Heard and One Humanity: From Labels to People

This article may be copied, quoted, or shared freely for non-commercial and educational purposes, provided that original authorship is acknowledged.

Images identified as “Public Domain” or “Artistic Impression” are free to share. For any third-party or museum images, readers should verify rights independently before reuse.

Website: www.darrenpalmerauthor.com

Support the Equality Without Distinction mission: gofund.me/712c849f0