Sappho — The Poet Who Refused to Be Silenced

Sappho: The Poet Who Refused to Be Silenced

History often records empires and armies. Sappho recorded the heart — and it survived.

Born on Lesbos around 630 BCE, Sappho became the most celebrated lyric poet of antiquity. Where epics praised kings and conquest, her poems sang of love, longing, and the charged intimacy of everyday life — often addressed to women. In a world that rarely preserved women’s voices, hers became unforgettable.

Life & Setting

Archaic Lesbos was a thriving hub of music, craft, and civic performance. Lyric songs — composed to be sung with the lyre — threaded through public rites, private gatherings, and festivals. In that world, poetry was not silent text but living voice: breath, cadence, memory.

Sappho flourished within this ecology of performance. Later sources place her in circles of women where education, ritual, and song interlaced. Whether we imagine a formal “school” or looser communities, the point stands: she wrote for listeners who knew her, for moments charged with presence. That social root matters — it explains the direct address, the immediacy, and the crystalline focus on lived emotion.

A Voice Set Apart

Greek epic cast its gaze on war and gods; Sappho turned the lens inward. She made intensity itself her subject — jealousy that shakes the body, love that outshines armies, beauty that arrests speech. In doing so she re-weighted what counted as worthy of song.

“Some say an army of horsemen… but I say it is what one loves.”

This was radical in two ways. First, lyric re-centered the I — not a boastful ego, but a precise instrument for feeling, image, and thought. Second, her poems often addressed women, acknowledging desire and admiration in ways later eras found threatening. She did not argue a thesis; she made us feel one.

Erasure & Fragment

Most of Sappho’s oeuvre vanished. Partly this is the fate of any ancient song tradition; partly it reflects shifting moral climates that found frank treatments of desire — especially between women — unacceptable. By the medieval period, she survived chiefly as quotations, paraphrases, and the thinnest of biographical notes in scholia and anthologies.

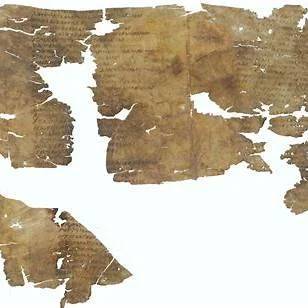

We inherit her voice as fragments on papyrus and as echoes in other people’s books. Yet even in pieces, the poems retain their voltage: a single image, the turn of a metaphor, a closing line like a heartbeat in the dark.

Sexualised Reduction

One of the few explicit references to Sappho in ancient lexicons comes through Hesychius, a 5th-century compiler of Greek words. In his dictionary, he preserves the term olisbos — a leather or ivory device used by women for pleasure — and connects it to her. This detail, drawn not from her own surviving verses but from the margins of male scholarship, has echoed disproportionately in how later generations remembered her.

The fact that Sappho’s legacy often survived through sexualised fragments tells us two things. First, it shows how male commentators filtered women’s voices, choosing what to preserve and what to dismiss. Second, it highlights why her poetry — so openly celebrating women’s love for women — was seen as dangerous in conservative eras. What she wrote as intimate, complex, and deeply human was flattened into stereotype, scandal, or moral lesson.

This is not unique to Sappho. Again and again, women in history are remembered through the narrowest lens, reduced to their sexuality rather than recognised for their broader contributions. That her name survives most loudly in this way says as much about the anxieties of later cultures as it does about her work. It is a reminder that erasure does not always mean silence; sometimes it means distortion.

Rediscovery & Influence

From the late 19th century, archaeological digs in Egypt — notably at Oxyrhynchus — began to yield papyri preserving lines and stanzas of Sappho. The 20th and 21st centuries added more surprises (e.g., the Cologne papyri; later “Brothers” and “Kypris” poems), sharpening the silhouette of a voice we thought we’d lost.

Translations shaped reception: Mary Barnard’s lucid 1958 English made Sappho modern; Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter (2002) honored the gaps — letting silence speak where the papyrus fails us. Poets such as Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich found kinship in Sappho’s clarity, precision, and refusal to apologise for desire.

Why Sappho Matters

Sappho reminds us that the archive is not neutral. What survives is shaped by taste, power, and anxiety. Yet even in fragments, her poems insist that the private is historical — that a woman’s voice, speaking of love and beauty, belongs in the same record that keeps kings and wars.

Equality Without Distinction asks us to value contribution over category. By that measure, a handful of Sapphic lines can be as historically consequential as a thousand lines of epic — because they recalibrate what counts as humanly significant. Her work widens the canon not as token inclusion but as a standard of excellence.

Fragments can still move the world. The point is not how much survives, but what it makes us see.

Further Reading

- If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho — trans. Anne Carson (2002).

- Sappho: A New Translation — trans. Mary Barnard (1958).

- Margaret Reynolds, The Sappho Companion (2003).

- On papyri & finds: The Oxyrhynchus Papyri; Cologne papyri; recent “Brothers” poem publications.

If this profile helped you see Sappho more clearly, share it — and help us keep forgotten voices in view.