When Evidence Allows More Than One Story

When Evidence Allows More Than One Story

When Evidence Allows More Than One Story

by Darren Palmer

This short piece exists for readers who paused out of curiosity — not for answers, conclusions, or certainty.

Archaeology is often presented as a process of discovery: evidence is found, analysed, and transformed into knowledge. In practice, it is more complicated than that. Evidence does not arrive with a story attached. It must be interpreted — and interpretation, however careful, is never neutral.

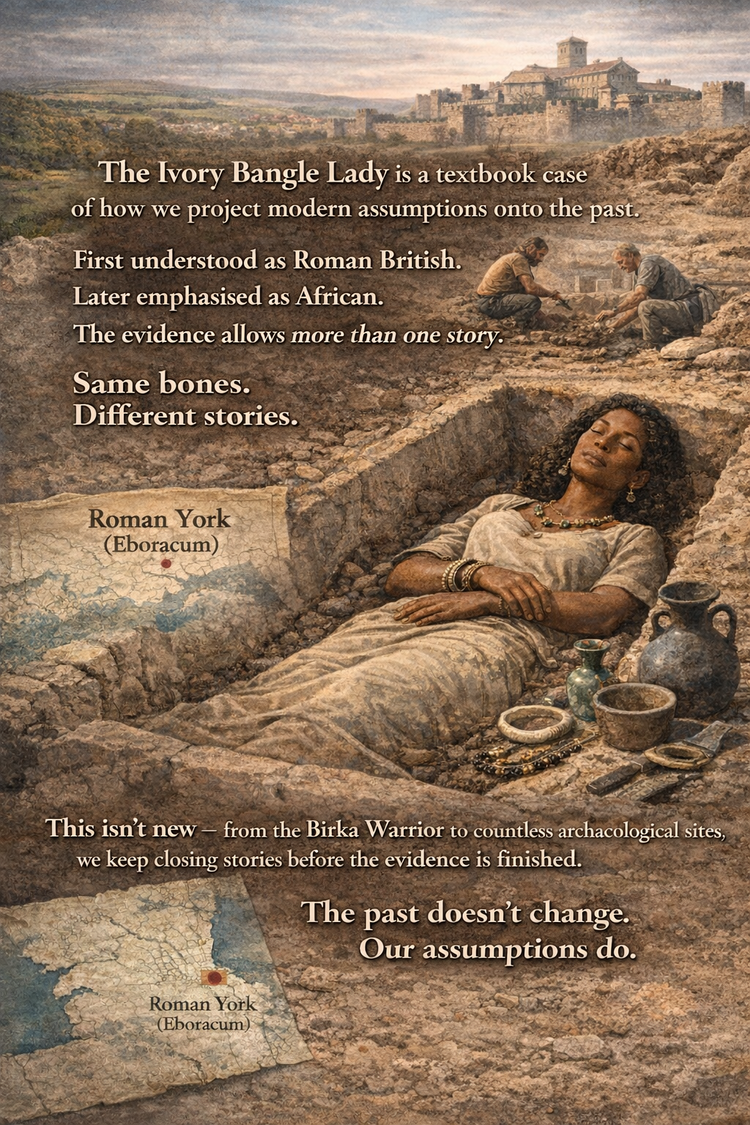

The case of the Beachy Head Woman has become a clear illustration of this problem. It is not important because one conclusion replaced another, but because it shows how confidently interpretation can settle before the evidence truly warrants it. That lesson matters when we turn to other well-known cases, including the individual known as the Ivory Bangle Lady.

This piece is not about replacing one interpretation with another. It is about understanding how easily assumptions form, how slowly they unravel, and why history requires a discipline of restraint.

A lesson from Beachy Head

The Beachy Head Woman was discovered near the cliffs of East Sussex and dates to the Roman period. Early assessments of her remains suggested African ancestry, based largely on skeletal morphology. Later isotope analysis pointed towards a childhood spent in the eastern Mediterranean. More recent ancient DNA analysis indicates a strong likelihood that she was local to south-west Britain.

The burial did not change.

The surrounding landscape did not change.

Only the interpretation did.

This was not a failure of archaeology. It was a demonstration of its limits. Each interpretation was reasonable within the knowledge and assumptions of its time. What changed was not the past, but the framework through which it was read.

Beachy Head shows how quickly provisional interpretation can harden into narrative — and how difficult it can be to soften again.

Introducing the Ivory Bangle Lady

The individual often referred to as the Ivory Bangle Lady was discovered in York, Roman Eboracum, during early twentieth-century excavations. She was buried in a stone coffin dating to the late 3rd or early 4th century CE. Her grave goods included a set of ivory bangles, along with jet and glass jewellery — materials associated with wealth and status in Roman Britain.

For much of the twentieth century, she was understood simply as a high-status woman living in Roman York. In recent decades, advances in scientific analysis have prompted a reassessment of her life.

That reassessment has been widely discussed, often with confidence. Before asking whether that confidence is justified, it is worth setting out clearly what the evidence supports.

What the evidence establishes

When stripped back to its most defensible claims, the evidence tells us a limited number of things.

- Osteological analysis indicates that she was biologically female.

- Ancient DNA analysis indicates African ancestry.

- Her burial context and grave goods indicate high social status.

- Her burial places her within Roman social and cultural structures in York.

This alone is significant. It demonstrates that ancestry did not preclude status, wealth, or integration in Roman Britain.

Isotope analysis suggests she may have spent part of her early life in a region with isotopic signatures consistent with climates warmer than Roman Britain.

These findings are careful, well-founded, and the product of improved methods. They deserve to be taken seriously.

They do not, however, compel a single life story.

The limits of what evidence can say

Evidence narrows possibilities; it rarely closes them.

- DNA tells us about ancestry, not birthplace or identity.

- Isotopes reflect childhood environments, not lifelong residence.

- Grave goods indicate status, not origin or self-understanding.

Isotope evidence, in particular, is often misunderstood. A non-local isotopic signature does not mean someone was born abroad and remained foreign. It may reflect childhood mobility, temporary residence elsewhere, or time spent moving within an empire where elite families frequently relocated for administrative, military, or economic reasons.

Beachy Head demonstrates that isotope readings can later be reinterpreted as baselines improve. That does not make isotope analysis unreliable — but it does mean it must be held provisionally.

Taken together, the evidence does not tell us:

- where the Ivory Bangle Lady was born

- how she identified herself

- whether she was an immigrant or a descendant of migrants

- how many generations her family had lived in Britain

- whether her childhood was spent in one place or several

These are not gaps to be filled with speculation. They are limits that must be acknowledged.

Uncertainty is not a weakness of history — it is its discipline.

Possibility without improbability

This is where the lesson of Beachy Head applies most strongly.

The responsible response to the Ivory Bangle Lady is not to replace one confident narrative with another, but to recognise that the evidence allows multiple plausible life histories.

- She could have been born in Britain and spent part of her childhood elsewhere within the empire.

- She could have been born abroad and moved to Britain at a young age.

- She could have belonged to a family that moved repeatedly due to imperial service.

- She could have returned to Britain later in life after childhood spent elsewhere.

None of these possibilities contradict the evidence. None of them require new data. None of them claim priority over the others.

They simply acknowledge what the evidence does — and does not — resolve.

Rome, belonging, and modern assumptions

Roman society was not organised around biological race in the modern sense. Belonging was structured around legal status, citizenship, freedom, and cultural participation. People from across the empire — North Africa, the Levant, Gaul, Britain — could be Roman in law and identity. Even emperors came from outside Italy.

This did not make Roman society equal. Enslavement and exclusion were real and often brutal. But ancestry alone was not a ceiling.

The Ivory Bangle Lady’s burial does not prove equality. It demonstrates integration. That distinction matters.

Modern readers often import contemporary ideas of race and identity into the past, compressing complex lives into symbolic categories. The archaeological record resists that simplification — if we allow it to.

A wider pattern: Birka and beyond

The Ivory Bangle Lady is not an isolated case.

The Birka Warrior, long assumed to be male based on grave goods associated with warfare, was later identified through DNA as biologically female. The evidence had always been present. What changed was the willingness to question the assumptions guiding interpretation.

In both cases, earlier conclusions were not irrational. They were shaped by precedent, expectation, and comparison with previous finds. Archaeology often relies on analogy — a structure resembles a temple, a burial resembles a warrior, a body resembles a known type.

But analogy is dangerous. As even popular programmes like Time Team have shown, buildings confidently identified as temples or ritual spaces have later been reinterpreted as domestic, industrial, or administrative. Familiar patterns encourage premature certainty.

Interpretation does not fail because evidence is weak. It falters when assumption goes unexamined.

Equality Without Distinction

Every archaeological interpretation is shaped by the people and institutions producing it — their training, culture, expectations, and historical moment. No interpretation is free from perspective.

The closest we can come to honesty is to enter historical inquiry with Equality Without Distinction: not privileging modern categories, national narratives, institutional authority, or inherited frameworks over the evidence itself.

This does not mean abandoning interpretation. It means holding it lightly.

History advances not by replacing one certainty with another, but by learning which questions we are not yet entitled to close.

Conclusion

The Beachy Head Woman teaches us how confidently we can misread the past. The Ivory Bangle Lady reminds us how easily evidence can be compressed into a single story. The Birka Warrior shows how long assumptions can survive unquestioned.

In every case, the danger is not error — it is certainty.

Evidence deserves patience. Interpretation deserves humility. And the past deserves to remain more complex than our need for neat conclusions.

Sometimes the most honest response to evidence is not an answer, but an allowance.

If nothing else, it is a reminder that the past often asks us to wait a little longer before deciding.